The Wisdom of "Don't Know" Mind

Too often when we don’t know something we become upset, particularly if

we feel we should know. Frequently,

the real problem here is not that we don’t know, but rather it is our not being

able to accept that we don’t know.

We feel like we have to know and we have to know right now. When we feel tense, agitated, and pressured

in this way it creates an obstacle to our ever knowing. The result is suffering.

Being able to simply accept that “I

don’t know” releases me. So does letting

go of the idea that I have to know.

It is a

relaxed mind that makes it possible to see creative solutions. Almost always, we can simply wait

patiently for clarity to arise/emerge spontaneously on its own.

Not knowing

is not the same as being confused. There

can be peace with not knowing: When I’m at peace with not knowing, I’m not

confused. I have clarity about the

fact that I don’t know, and I fully accept that I don’t know right now. It’s ok to not know, and I’m not confused

about that.

We think we

must know, and yet knowledge can actually be a barrier to learning. Often when we hear a new idea, we reflexively

compare it to what we already know (or think we know). If the idea agrees with our existing

knowledge, we accept it as true. If it

doesn’t agree, then we reject it as false.

Either way, we learn nothing and remain stuck in our existing ideas and

prejudices.

But it is

possible to learn to drop what we know and enter into a state that Zen

teacher Shunryu Suzuki calls beginner’s mind:

In the expert’s mind there are few possibilities; in the beginner’s mind

there are endless possibilities.

Sometimes

it is the person with no experience or knowledge who can come in completely

fresh and without preconceptions, and therefore see clearly what needs to be

done. Think of the mind as being like a filing cabinet. When

you start life, you have only empty file drawers with no information in them. When

you are presented with a bit of new information, it simply goes anywhere in in

one of the drawers.

As we learn and get more and more information, we create file folders and we use these to categorize incoming information, thereby making it easier to find when we need it. This is useful. However, it also has the down side that we tend to see things in terms of what we already know, and we try to fit the new observations into the filing system we already have. If they don’t fit in, we may discard them—or not even see them at all—and lose out on something important.

Our file system is not good in another way, in that it causes us to see the present in terms of the past and in terms of set categories, thus preventing us from seeing new arrangements of information and new solutions. We try to solve problems using the problem types and problem solutions we already have in our file cabinet. It goes like this: Using my file of “Toxic Spill-Types” I identify what I have in front of me as a “Type X Spill.” Then I look in my file folder of “Solutions to Type X Toxic Spills” and select the best existing solution-type in the folder and apply it to the situation in front of me. This approach often works, but it also prevents us from seeing the creative and better solutions we might see if we are able to look at things from the standpoint of beginner’s mind.

Someone who has little knowledge of the situation, or who can temporarily let go of their existing knowledge, can come at situations from a totally new and fresh perspective, and because of this can see parts of the situation that the expert is blinded from seeing—blinded by his existing knowledge.

It is

possible to choose to temporarily enter a state of mind in which our

habit of using past knowledge to make snap judgments of new ideas can be set

aside. This is difficult at first for

most people, but it is a learned skill that anyone can acquire.

What is

needed is to develop the patience required to simply hold a new idea in

one’s mind without either agreement or disagreement. Suppose I am at a friend’s house and he is

using a bread machine. I’ve never used one

and I’m intrigued. As it turns out, my

friend has two bread machines and is considering selling one of them: would I be interested? Maybe…

So my friend says to me, “Just take it home with you for a week or two

and try it out; if you like it, you can buy it and if not just bring it

back.” So I take it home.

So

here is my situation. I am holding the bread

machine in my home, but I haven’t bought it and it’s not mine. I haven’t decided that I won’t buy it,

either—there is simply no commitment one way or the other. I am in a state of “don’t know” mind. There is curiosity, and the desire to simply

turn this new thing over in my mind and look at it from all sides. I am in a position to try it out for a while;

and my intention is simply to get to know it better, understand how it works

and see what value it might have in my life. I might even do some research or

talk to other people. Later on, if I

want, I can decide I want to buy it, or decide not buy it, or decide I simply

need to spend more time with it before deciding anything.

This is

exactly like holding a new idea in my mind—I am trying it out, getting

acquainted with it, taking it for a test drive.

I am not agreeing with it (“buying it”) or disagreeing with it (“not

buying it”). There really is no pressure

and nothing to argue about. This puts me

in the best possible position to learn something new.

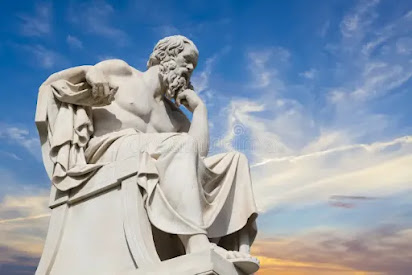

Socrates could

tell us something about this. When Socrates talked the oracle at Delphi,

he was told that he was the wisest person alive. This puzzled him greatly, because he thought

he knew very little. He decided to

investigate by seeking out and talking to people in Greece who had a reputation

for being knowledgeable. First, he

talked to the poets and, upon being questioned, the poets turned out not to

have any real knowledge at all—they were just clever with words. Next, he questioned the politicians, and

discovered that they, too, didn’t really know anything. Finally, Socrates talked to people in the

practical arts—builders, craftsman, farmers—and found that they actually did

have real knowledge. But, when he questioned

them further, he discovered that they all made the mistake of thinking that

their technical expertise somehow made them experts in other areas. Because of their technical knowledge, they

thought they also had knowledge of nontechnical subjects such as philosophy,

government, human emotions, art, and more. When Socrates questioned them, he found that

they actually knew nothing about any of these other subjects.

From

all of the above, Socrates came to the conclusion that maybe he was the wisest

person alive because at least he did not think he knew things that he didn’t

know. He at least knew what

he did not know and was therefore open to learning.

Note: My intention is to add

new posts to the blog approximately every 2 to 3 weeks. If you would like to

receive an e-mail notification each time a new blog post is made, please let me

know and I will add you to the list of recipients. This notification will also

include the title of the new post. Some of the material that appears in

this blog is copyrighted, but in keeping with the Buddha’s teaching that the

dharma is not to be sold, the contents of this blog may be freely copied and

given away, but not sold.

If you have questions, comments, or ideas for new Blog topics please

contact Dale at ahimsaacres@gmail.com.

Comments

Post a Comment